By Muhamad Ali

A paper for discussion at the Center for the Languages and Cultures, UIN Jakarta, April 2005

Pluralism still needs further and wider discussion among various elements in Indonesia, not only because of its condemnation by the Council of Indonesian Ulema, of the condemnation and attacks against the marginalized movement of Ahmadiyah, and of the forced closure of over 200 churches by the Islam Defender’s Front (FPI) since 1996 to date, but also because of the complexity and changes of its very term in the intellectual history of modern societies. Franz Magnis-Suseno’s article “Defining Pluralism, Liberalism, Secularism” has been particularly insightful in stressing the value of pluralism and its difference from relativism, but it will be useful to understand that the vocabulary of pluralism has changed and differed according to time and space.

It is true that we do not have to agree in what pluralism means and it never has one monolithic denotation. “Words”, says French philosopher Claude Levi-Strauss, “are instruments that people are free to adapt to any use, provided they make clear their intentions.” In the social sciences, as in philosophy and religion, there are wide and frequent variations in the meaning of the simplest words, according to the thought that uses and informs them.

The use of the state or the religious authority to enforce particular understanding of religion is one thing, but the disagreement on the meaning of the terms (such as pluralism) is another thing, which we should scrutinize further.

The forced closure of 23 churches in Bandung between September 2004 and August 2005 by the Islam Defender’s Front (FPI), and over 200 churches since 1996 raises questions: to what extent can churches be regarded as harming the Muslim environment or social order? Does one religious community have the right to convert other religious communities and what should the government do about this? Can we tolerate the intolerant groups like FPI?

Pluralism means differently and dynamically. In one definition, it is diversity that denotes a fact, a condition, a reality of difference, while pluralism is an ideal or impulse, the acceptance and encouragement of diversity. In another, pluralism is a state of society in which members of diverse ethnic, racial, religious, or social groups maintain an autonomous participation in and development of their traditional culture or special interest within the confines of a common civilization. It can also be defined as a concept, doctrine, or policy advocating this state. Thus, Pluralism is defined not as diversity itself but as one of the various things people do and think in response to diversity (Wesbter’s Third International). This notion of pluralism did not emerge until the 1920s.

Pluralism can be seen from different levels: first, pluralism as toleration (absence of persecution, the right of a deviant to exist), pluralism as inclusion (to include outsiders, but not yet equal), and pluralism as participation (a mandate for individuals and groups to share responsibility for the forming and implementing of the society’s agenda. (William R. Hutchison, Religious Pluralism in America, 2003)

In the political context, pluralism is the belief in the distribution of political power through several institutions which can limit one another’s action, or through institutions none of which is sovereign. Pluralism is the advocacy of a particular kind of limited government. Second, pluralism is the belief that the constitution of a state ought to make room for varieties of social customs, religious, and moral beliefs, and habits of association, and that all political rights should be traced back to the constitution, and not to any social entity other than the state itself. In such circumstances the social and the political are as separate as can be, and uniform political institutions coexist with a plural society (a civil society in which several societies coexist in a single territory, interacting in a peaceful way, perhaps so as to become socially, politically, and economically interdependent). And third, pluralism is any view which, in opposition to monism (and to dualism), argues for a multiplicity of basic things, processes, concepts or explanations. (Roger Scruton, A Dictionary of Political Thought, 1996)

Pluralism, Religious Pluralism, Multiculturalism As Practices and Concepts

During the 18th century: French and German Enlightenment and Particular Meaning of Pluralism: liberalism, against absolutism of the Church, Jean-Jacques Rousseau (Social Contract, Civil Religion)

In the U.S., diversity happened to American religion in the first half of the 19th century, but pluralism as a concept did not arrive until the second half of the 20th century.

During the 19th century: pluralism as toleration; Protestant dominance continued; peoples were “in harmony and good neighborhood, no disputes about religion, nearly complete absence of polemical strife and bitterness in the religious life” (Crèvecouer) “the Christian, the infidel, the Mohammadan, the Jew, the Deist, has not only all his right as a citizen, but many have his own form of worship, without the possibility of any interference from any policeman or magistrate, provided he do not interrupt, in so doing, the peace and tranquility of the surrounding neighborhood” (Robert Baird, 1840s) “if you were a cultural outsider, you could be about as different as you wished in actual religious views. And it meant that if you were an outsider, acceptance depended to a large extent upon your willingness to adjust, to become assimilated, especially in matters of religious and general behavior.” “in the U.S, Christian sects are infinitely diversified and perpetually modified; but Christianity itself is an established and irresistible fact.” (Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, 1834-40).

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries: pluralism as inclusion; nonmainstream sectarians, Catholics, Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, Hindus, to be recognized and included as part of the society (given a voice, but not beyond that), Reform Judaism and Inclusionary Pluralism: “We recognize in every religion an attempt to grasp the Infinite One”, Liberal Catholics and the Quest for Inclusion, the World’s Parliament of Religions (1893) as a showcase for inclusion.

Mid-20th century: New Mainstream, New Pluralism, Pluralism as participation: Protestant establishment of old was sharing its mainstream status with the other two major faiths (Catholics and Judaism). Islam nearly matched Judaism (6 millions in size)

Contemporary America: Whose America? A. Samuel Huntington “Who are We: The Challenges to American National Identity” (2004), reasserts Protestant roots of America. The challenges to American identity are subnational identities, immigrants, assimilations, militant Islam. B. Willaim Hutchison’s Religious Pluralism: “We should accept pluralism as a primary value, but that we must also deal seriously with pleas concerning social and moral cohesion.”, beyond inclusion, that is mutually respectful and nonpatronizing.” One still hold to his or her own convictions, does not mean lack of all conviction. Not to say we are chosen and you are not “ “.voluntary, mono or multiple identities.” Renewed civil religion. “Recognition by both religious and nonreligious peoples that the days are past when any one group can dictate a comprehensive public philosophy that will prevail for the whole of the people (Prof. Marsden, 1990), Civil Religion (Robert Bellah, 1970s) Thus, Religious Pluralism as a Work in Progress in the U.S.: advanced pluralist thinking has now gone beyond mere toleration and mere inclusion, although intolerance and exclusion persist. (Hutchison, 2003) Some regard pluralism as dangerous loss of consensus and social cohesion, but Hutchison sees pluralism and social cohesion can coexist

Religious Pluralism: Some Definitions

“All religions are the relative- that is, limited, partial, incomplete, one way of looking at thing. To hold that any religion is intrinsically better than another is felt to be somehow wrong, offensive, narrow-minded; Deep down , all religions are the same – different paths leading to the same goal.” (Paul Knitter, No Other Name? A Critical Survey of Christian Attitudes toward the World Religions, 1985)

“Transcendent Unity of Religions” (Frithjof Schuon, 1984)

“Other religions are equally valid ways to the same truth” (John Hicks)

“Other religions speak of different but equally valid truths” (John B. Cobb Jr.)

“Each Religion expresses an important part of the truth” (Raimundo Panikkar)

Pluralism and Liberation (Farid Esack, 1997)

Multiculturalism: Some Definitions

Pluralism and multiculturalism are often overlapped, used interchangeably, but sometimes both mean different things, pluralism can have religious as well as cultural non-religious dimension, but multiculturalism more specifically implies cultural (ethnic, racial, social) diversities.

Multiculturalism emerges from the mid-20 century. Multiculturalism signifies the approach which tries to give as much representation as possible, within legal, political, and educational institutions, to minority cultures. Multiculturalism poses a threat to the social order, removes the foundations for civil obedience. Multiculturalism constitutes an attempt to reduce Western civilization to the status of a culture. The principle influence of multiculturalism has been on the curriculum, especially in the universities, where multiculturalists argue that study in the humanities has focused exclusively on the work of dead white European males and ignored the achievements of other cultures. (Roger Scruton, A Dictionary of Political Thought, 1996)

Neither universities or policies can effectively pursue their valued ends without mutual respect among the various cultures they contain. Some differences – for example, racism and anti-Semitism – ought not to be respected even if expressions of racist and anti-Semitic views must be tolerated; Multicultural societies and communities that stand for the freedom and equality of all people rest upon mutual respect for reasonable intellectual, political, and cultural differences. (Amy Gutmann, Multiculturalism, 1994)

In the private sphere: my own identity crucially depends on my dialogical relations with others. In the public sphere, politics of multiculturalism, politics of recognition, politics of universalism (difference-blind fashion), politics of difference, politics of equal dignity: individualized identities, the notion of authenticity, equalization of rights and entitlements (Charles Taylor, “Politics of Recognition”, in Multiculturalism, 1994)

Pluralism, Religious Pluralism in Indonesia

Religious pluralism is equally complex concept; it is a Western word, but Indonesia has similar term signifying pluralism: Bhineka Tunggal Ika, Pancasila as the state philosophy, dipahami berbeda-beda, sering menjadi alat kekuasaan untuk mempertahankan status quo atau mainstream

Persoalan-persoalan antarumat beragama di Indonesia sangat komples: Kristenisasi dan Islamisasi, perkawinan beda agama, doa antaragama, pengadilan agama, pendidikan, Tujuh patah kata Piagam Jakarta, bentrok fisik Kristen-Islam,

Indonesian Scholarship on pluralism:

Nurcholish Madjid: pertama, sikap yang ekslusif dalam melihat agama lain (agama-agama lain adalah jalan yang salah, yang menyesatkan para pengikutnya), keduam sikap inklusif (agama-agama lain adalah bentuk implisit agama kita), dan ketiga, sikap pluralis (Agama-agama lain adalah jalan yang sama-sama sah untuk mencapai Kebenaran yang Sama, Agama-agama lain berbicara secara berbeda tetapi merupakan kebenaran-kebenaran yang sama sah, setiap agama mengekspresikan bagian penting sebuah Kebenaran), dialog antaragama berbasis keyakinan kepada seluruh para nabi dan rasul, syir’ah dan minhaj yang berbeda-beda, berlomba-lomba dalam kebajikan. (Nurcholish Madjid, 1998)

Pluralisme tidak dapat dipahami hanya dengan mengatakan masyarakat kita majemuk, pluralisme juga tida boleh dipahami sekedar kebaikan negative, sekedar menyingkirkan fanatisme, pluralisme harus dipahami sebagai pertalian sejati kebinekaan dalam ikatan-ikatan keadaban (genuine engagement of diversities within the bonds of civility) (1999)

Alwi Shihab: toleransi awal dari pluralisme. 1. pluralisme tidak semata menunjuk pada kenyataan adanya kemajemukan, harus ada keterlibatan aktif, 2. pluralisme harus dibedakan dengan kosmopolitanisme (kota Kosmopolitan tanpa interaksi aktif), 3. pluralisme tidak sama dengan relativisme (semua agama adalah sama), 4. pluralisme agama bukan sinkretisme. Seorang pluralis membuka diri, belajar dan menghormati penganut lain, tapi committed terhadap agama yang dianutnya (Islam Inklusif, 1997)

Budi Munawwar Rahman: Islam Pluralis (2001), Muhamad Ali, Teologi Pluralis-Multikultural (2003)

Conclusions

Pluralism is a complex but useful concept in explaining many issues related to human interaction and relationships;

Pluralism, religious pluralism, multiculturalism each means different thing for different people, but it has basic common notion: acceptance of the existence of diversity; the reading of texts and the role of context shapes such plurality of definitions of religious pluralism; Religious pluralism is never purely religious matter; it involves politics for the large extent

Religious pluralism in the context of Indonesia should be fundamentally agreed by the government and civil society, but its application can be contextual; the challenge remains, that is how to reconcile between recognition of difference and respect of universal substantive values.

As suggestion, we need to develop comparative religions/history of religions, national history of religions, world history of religions, studies of local cases of interfaith meetings and dialogues, interreligious prayers, interfaith marriages, religious pluralism and law, pluralism and education, studies of the history of religious pluralism in Indonesia, and other pluralism-related issues.

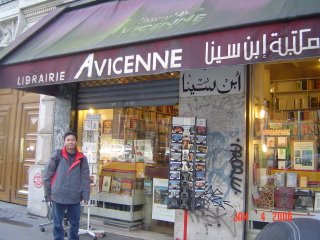

Photo: in a Buddhist Temple, Kelantan, Malaysia, with Abdullah Che Tengah, June 2005