The Jakarta Post, March 2, 2005

Muhamad Ali

What would most people think when they read or hear the phrase Islamo-Christian Civilization? Many Muslims and Christians would likely bristle at the very idea it seems to embody, and others will look suspiciously at the omission of “Judeo-“ from the phrase. Many more would suspect that this is simply impossible theologically and historically. Why Islamo-Christian Civilization?

Aren’t Christianity and Islam distinct and separated theologically and historically?

Challenging Huntington’s Clash of Civilizations, Prof Richard Bulliet wrote an enlightening work entitled “The Case for Islamo-Christian Civilization” (2004). Such phrases as Children of Abraham, Semitic Scripturalism, or Abrahamic Religions seem to do quite well for the Islamo-Judeo-Christian Civilization, but an Islamo-Christian civilization implies that Muslims and Christians shared the past, present and future. Conventional wisdom maintains that the differences between Islam and Christianity are irreconcilable. Bulliet looks beneath the rhetoric of hatred and misunderstanding to challenge the prevailing and misleading views of Islamic history and Clash of Civilizations. Bulliet argued that the sibling Christian-Muslim societies begin at the same time, go through the same developmental stages and confront the same internal challenges. Yet as Christianity grows rich and powerful, Islam finds success around the globe but falls behind in wealth and power.

According to Bulliet, the term Islamo-Christian civilization denotes a prolonged and fateful intertwining of sibling societies enjoying sovereignty in neighboring geographical regions and following parallel historical trajectories. Neither the Muslim nor the Christian historical path can be fully understood without relation to the other.

There is still a tendency to say that Muslims are less open to new ideas than Christian Westerners and that Muslims are more prone to conflict between themselves and to hate non-Muslims. Many Westerners often view the actual life of backward, poor, and sometimes violent Muslims in the light of the ideal peaceful separation between religion and the church in the West. On the other hand, many Muslims still blame the West as the cause of their backwardness materially and their moral crisis simply by referring to, for example, sexual freedom appearing in mass media. As Bulliet suggests, Westerners characterize militant Muslims as the dominant voice and scarcely recognize the presence of moderate and liberal minds. Muslims on the other hand, see the West as the secular land of sin, salesmanship, and superficiality. Both sides seem unaware of the admirable positive qualities that most Muslims and Westerners exhibit in their daily life.

Westerners do not include Islam in their civilization mainly because they are heirs to a Christian construction of history that is deliberately exclusive. Western Christendom regards Islam as a malevolent Other for many centuries and has invented any number of reasons for holding this view.

In the academic circle in the West, we tend to read European or Western history in Euro-centric perspective as if the world is only the West. On the other hand, Muslims have their own historical reading as if there is only an Islamic history and there is no interaction between them and others. I have not find any single work on world history considering Islam, Christianity and others as one historical actor in a shared civilization. In other words, there is no a truly shared world history being written and promoted.

In Indonesia, historiography tends to be exclusive. For example, Christianity has been regarded as a colonial religion; a religion that was carried and preached by the Dutch colonials –and English, Germans, Americans. This has become the main obstacle for mutual understanding among Muslims and Christians in Indonesia. The historical fact is that Christianization is not always part of colonial enterprises. There were Christians who opposed Dutch colonialism; and when some of them did not they were engaged in education and cultural development. Many of them were independent missionaries, just like Muslim preachers. Understanding this more objective history is crucial in rehabilitating hidden distrust between Muslims and Christians.

It is true that the majority of Indonesians today are Muslims, but this does not necessarily mean that non-Muslims, including Christians did not play a part in Indonesian independence and postcolonial local and national development. Majority-minority perspective has often obscured the fact that significant contribution to shared economic, cultural, and political development has been continuously made by different religious leaders and communities.

Indonesia has actually witnessed peaceful coexistence between different religious communities. News reports and scholarly research on inter-religious conflicts as taking place in some parts of Indonesia should not overlook the more consistent and wider-range situation of inter-religious cohabitation. Religious civil societies have been promoting peaceful coexistence, but non-specifically religious organizations and individuals, often without any religious affiliation, have equally demonstrated how they could work together in their economic, educational, political and cultural activities.

Such economic, political, and cultural shared experiences are the best example of how Islamo-Christian civilization in Indonesia is neither something foreign nor impossible to maintain in the future. In social, economic, and political relationships, Muslims and Christians have long collaborated in both local and national levels. This kind of Islamo-Christian civilization that Richard Bulliet envisages has apparently worked quite well in Indonesia, but a shared religious history in which Muslims, Christians as well as other religious communities played the same role is still far from reality. A challenging effort is how to establish a shared history of civilization in which Christian and Muslim cultures are actually integrated in Indonesia.

In addition, religious pluralism in the sense that good Christians and Muslims are not infidels to each other and that good Christians and Muslims can get salvation and happiness is much more difficult for Muslims and Christians to adhere. For example, a Christian who works with a Muslim in a company can be very friendly, but when it comes to their belief they tend to regard the others as infidels and not worthy of salvation in the hereafter.

Therefore, to suggest an Islamo-Christian civilization should consider different levels of human relations: material-economic, but also religious-moral. Our challenge is how to rethink our own belief in light of other beliefs and to reinterpret our ritualistic and textual texts in light of more contextual, general and shared reading of history. Thus, to be tolerant is not simply to pretend to be good to other religious individuals and communities at the social and economic levels, but also to regard the others as we regard ourselves in terms of God’s salvation and blessings here in the world and in the hereafter.

The idea of Islamo-Christian civilization is constructive (and can be widened to include other religions too), but it rests more immediately on the need of more specifically Christians and Muslims in Indonesia and elsewhere to find common ground at a time when suspicion, fear, draconian government action and demagoguery increasingly threaten to divide them.

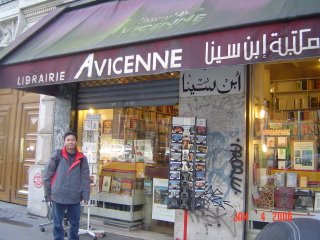

The photo: in front of a bookstore called Avicenne in Paris, Dec 2005

No comments:

Post a Comment