Pope, Islam and future of interfaith dialog

The Jakarta Post, 21 September 2006

Muhamad Ali

Pope Benedict XVI's controversial comments on Islam at the University of Regensburg, Germany, despite his prompt apology, has left us some crucial issues to rethink in terms of promoting interfaith dialog.

I have tried to understand why the pope made a reference to Islam when he was talking about Christian belief, reason and Western civilization, and now better understand why he was upset by the unexpected reaction to his comments and later regretted his words.

Before becoming pope, the then Cardinal Ratzinger wrote in 2004 that Christianity should be revitalized amid a secularizing Europe and West. The Hellenistic civilization influenced Byzantine, and led to the establishment of a continent that would eventually become the basis for Europe.

For Benedict, there are spiritual and rational roots in Europe and the West in general that should be defended and revitalized. In his controversial speech, Benedict intended to put into context the historical connections between those great civilizations and Western Christian civilization, and he found this context in a 14th century conversation between a Byzantine emperor and a Persian scholar representing a rival civilization of the time. In his speech, the pope seemed to be trying to bridge the gap between secularists and Catholics.

Adel Theodore Khoury, the editor of the book Polimique Byzantine contre l'Islam, said what the pope quoted was actually an advocation for genuine harmony among Abrahamic believers. According to Khoury, "Membership in the posterity of Abraham can foster an open encounter between the faithful of the three Abrahamic religions."

"...Rather than being an object of dispute and wrangling between the three faiths that claim him, Abraham can become the initiator and the guarantor of a serious dialog between them and of a fruitful cooperation for the good of all humanity."

Thus, in my reading, the pope's selection of the quote was more likely motivated by his intention to provide a context, not an opinion.

For many Muslims, however, the problem with the speech was that the selected quotation failed to portray a complex relationship between Islam and reason, merely for the purpose of reasserting the compatibility of Catholicism with Hellenistic rationality.

In retrospect, the pope could have quoted other phases and sides of history which provide more complex and diverse experiences of the relationship between Muslims and Christians in connection with faith and reason.

In the medieval history of Islam, many Muslim scholars, philosophers, Sufis and theologians believed in the compatibility between Islamic belief and reason, progress and humanism, despite others who believed otherwise. There are also the histories of peace and coexistence between Muslims, Christians and Jews in Europe, the Middle East, Asia and all over the world. In fact, shared and connected civilizations have long existed in parts of the world.

Religion is a complex historical and theological phenomenon. Catholicism, Islam, Judaism and other religions (and secular ideologies) have dark histories -- of polemics, conflicts and wars -- that everyone should realize and understand as part of world history. Religious believers keep the faith that their religions are essentially good. Yet, double standards have occurred: many Catholics may emphasize the normative ideals of their religion while pointing to the bad practices of other religious communities. Many Muslims say and write about the normative ideals of their religion, while at the same time criticizing the bad practices of Christians and Jews. Self-criticism is a very rare practice among believers, although it is crucial in terms of bridging the perception gaps and creating peaceful coexistence.

The pope's speech was not his first on Islam. In Cologne on Aug. 20, 2005, Benedict delivered a speech to the Muslim community. His major concern was the spread of terrorism in the name of religion, and he said, "I know that many of you have firmly rejected, also publicly, in particular any connection between your faith and terrorism and have condemned it. I am grateful to you for this, for it contributes to the climate of trust that we need. The life of every human being is sacred, both for Christians and for Muslims."

He reaffirmed that "the Church wants to continue building bridges of friendship with the

followers of all religions, in order to seek the true good of every person and of society as a whole" (L'Osservatore Romano, April 25, 2005).

For Benedict, the Magna Carta of the dialog with Muslims remains the Second Vatican Council: "the Church looks upon Muslims with respect. They worship the one God living and subsistent, merciful and almighty, creator of heaven and earth, who has spoken to humanity and to whose decrees, even the hidden ones, they seek to submit themselves whole-heartedly, just as Abraham, to whom the Islamic faith readily relates itself, submitted to God ..." (Declaration Nostra Aetate, n.3).

Not to repeat the mistakes of the Crusades should not mean not learning from and studying the history. Many studies on the Crusades have uncovered many revealing facts as well as mysteries. The Crusades have tended to be viewed from partial perspectives, from the Muslim side or from the Christian side (Carole Hillenbrand, The Crusades: Islamic Perspectives, 1999).

There are certainly more theological and ethical issues that Muslims, Christians and all others need to discuss in facing the complex challenges of modern or postmodern times. As Benedict said in 2005: "Dear Christians and Muslims, we must face together the many challenges of our time. There is no room for apathy and disengagement, and even less for partiality and sectarianism ... interreligious and intercultural dialog between Christians and Muslims cannot be reduced to an optional extra. It is in fact a vital necessity".

The great historian Arnold Toynbee once said that the fate of a society always depends on its creative minorities. Muslims, Christians, Jews and others, in their respective countries everywhere, should play their roles in helping the world into peace and prosperity.

The future of interfaith dialog is still bright if everyone is sincere and serious, and Pope Benedict XVI has given a very valuable example for everyone about sincerity, empathy and seriousness in dialog and mutual understanding.

The writer is a PhD candidate in history, a fellow at the East-West Center and a lecturer at State Islamic University, Jakarta. He can be reached at muhali74@hotmail.com.

A Reader's Response to the Above Article

The Pope and Islam Saturday, October 07, 2006

It is a sweet irony that while according to some the Pope's Regensburg address is suggesting that there may be a contradiction between Islamic faith and logos, the most reasonable reaction so far, in my opinion, has come from an Islamic intellectual, Muhamad Ali.

My congratulations to him. At least someone has really read and understood this controversial lecture. Of course there is always room for interpretation and reading between the lines, like some ideologists eagerly do.

Nevertheless, a less sweet irony is that while the lecture was about the relation between faith and reason, many Muslim religious and political leaders have angrily condemned the Pope for "insulting the Muslims" and have repeatedly asked for an apology.

If they condemn someone without really knowing the facts, then where is "reason"? And wouldn't that make the Pope's lecture very relevant too? Separate faith from reason, add a media which seems to rather play the role of "news and sensation maker" instead of "reporter of facts", and hatred, distrust, violence and even the killing of an innocent nun results.

Another interpretation of the Regensburg address is that it accuses Islam of promoting violence. So what were those people, who call themselves Muslims, who reacted violently, trying to prove? Right, there is some basic rationality, logos, missing in their reasoning.

Now let me say in honesty -- and the truth sometimes hurts but we can learn from it -- that many people in Europe have gotten a less favorable opinion about Islam and Muslims as a result of the reactions (including those of respected leaders) to the Pope's lecture.

People like Muhamad Ali, the majority of Indonesian Muslims, as well as the rich scholarly tradition of Islam and science, prove that Islam, reason, tolerance and peacefulness can go together perfectly.

Furthermore, Muslims have the right to ask the same questions substituting Islam by Christianity or Western secularism and they do. For example, we are regularly reminded of the crimes of the Crusaders, Western (Christian) colonization, the present day suffering of Muslims in for instance the Palestinian territories, Southern Thailand, Chechnya, Kashmir and the inability of the West to deal with this. They are right to do so. But similarly, non-Muslims should have the right to remind Muslims of their dark pages in history as well as the suffering in Darfur, the long Shiite-Sunni conflict, Papua, and with -- what they perceive as -- the inability of the Muslim world to deal with terrorism and fanaticism which are just as well factors in the deadlock of several conflicts.

It should be clear that they are talking not about Islam as a faith but about something completely different. Muslims should acknowledge that and respect that too. In fact, it would be helpful if they would realize that the real insults to Islam are those people or entities who claim to be Islamic but practice un-Islamic acts.

SIMON P. WARREN, Reading, UK

Wednesday, September 20, 2006

Friday, September 15, 2006

Pope's remarks on Islam

Pope's remarks on Islam shows how he should have learnt more about the history and teachings of Islam, about the diversity of meaning of jihad. He should have not talked about Islam if he merely quotes. It is regretable that in the situation where there has been already a huge gap between Muslims and others in the West, Pope made such careless remarks in Germany reported throughout the world. On the other hand, Muslims do not need to show their disagreement in violent ways; what they need to do is learning more about the history of Islam, about the meaning of jihad and other misunderstood terms, and learning more about the history of other religions. Comparative religions is a subject undevelopped in all countries, in the West and in the Muslim world. Mutual respect and mutual understanding do not come from ignorance and carelessness. They come from endless learning and dialogue.

Hale Manoa, September 15, 2006

Muhamad Ali

=======================

Muslim anger grows at Pope speech

www.bbc.co.uk , September 15, 2006

The Pope's comments came on a visit to GermanyA statement from the Vatican has failed to quell criticism of Pope Benedict XVI from Muslim leaders, after he made a speech about the concept of holy war.

Speaking in Germany, the Pope quoted a 14th Century Christian emperor who said Muhammad had brought the world only "evil and inhuman" things.

Pakistan's parliament passed a resolution on Friday criticising the Pope for making "derogatory" comments.

The Vatican said the Pope had not intended to offend Muslims.

"It is clear that the Holy Father's intention is to cultivate a position of respect and dialogue towards other religions and cultures, and that clearly includes Islam," said chief Vatican spokesman Federico Lombardi in a statement.

But in spite of the statement, the pontiff returned to Rome to face a barrage of criticism, reports the BBC's David Willey in Rome.

The head of the Muslim Brotherhood said the Pope's remarks "aroused the anger of the whole Islamic world".

Violence and faith

In his speech at Regensburg University, the German-born Pope explored the historical and philosophical differences between Islam and Christianity, and the relationship between violence and faith.

The remarks do not express correct understanding of Islam

Mohammed Mahdi AkefMuslim Brotherhood

Stressing that they were not his own words, he quoted Emperor Manual II Paleologos of the Byzantine Empire, the Orthodox Christian empire which had its capital in what is now the Turkish city of Istanbul.

The emperor's words were, he said: "Show me just what Muhammad brought that was new and there you will find things only evil and inhuman, such as his command to spread by the sword the faith he preached."

Benedict said "I quote" twice to stress the words were not his and added that violence was "incompatible with the nature of God and the nature of the soul".

'Angry and hurt'

Pakistan's parliament passed a resolution demanding that the Pope retract his remarks "in the interest of harmony between religions".

"The derogatory remarks of the Pope about the philosophy of jihad and Prophet Mohammed have injured sentiments across the Muslim world and pose the danger of spreading acrimony among the religions," the AFP news agency quoted the resolution by the country's national assembly as saying.

Meanwhile, the "hostile" remarks drew a demand for an apology from a top religious official in Turkey - where the Pope is due in November on his first papal visit to a Muslim country.

Ali Bardakoglu recalled atrocities committed by Roman Catholic Crusaders against Orthodox Christians and Jews, as well as Muslims, in the Middle Ages.

In Egypt, Muslim Brotherhood head Mohammed Mahdi Akef said the Pope's words "do not express correct understanding of Islam and are merely wrong and distorted beliefs being repeated in the West".

In a statement, he was "astonished that such remarks come from someone who sits on top of the Catholic church which has its influence on the public opinion in the West".

Sheikh Youssef al-Qardawi, a prominent Muslim cleric in Qatar, rejected the Pope's comments, in remarks reported by Reuters.

"Muslims have the right to be angry and hurt by these comments from the highest cleric in Christianity," Mr Qardawi reportedly said.

"We ask the Pope to apologise to the Muslim nation for insulting its religion, its Prophet and its beliefs."

The 57-nation Organisation of the Islamic Conference also said it regretted the Pope's remarks, and news agencies reported a furious reaction on Islamic websites

Hale Manoa, September 15, 2006

Muhamad Ali

=======================

Muslim anger grows at Pope speech

www.bbc.co.uk , September 15, 2006

The Pope's comments came on a visit to GermanyA statement from the Vatican has failed to quell criticism of Pope Benedict XVI from Muslim leaders, after he made a speech about the concept of holy war.

Speaking in Germany, the Pope quoted a 14th Century Christian emperor who said Muhammad had brought the world only "evil and inhuman" things.

Pakistan's parliament passed a resolution on Friday criticising the Pope for making "derogatory" comments.

The Vatican said the Pope had not intended to offend Muslims.

"It is clear that the Holy Father's intention is to cultivate a position of respect and dialogue towards other religions and cultures, and that clearly includes Islam," said chief Vatican spokesman Federico Lombardi in a statement.

But in spite of the statement, the pontiff returned to Rome to face a barrage of criticism, reports the BBC's David Willey in Rome.

The head of the Muslim Brotherhood said the Pope's remarks "aroused the anger of the whole Islamic world".

Violence and faith

In his speech at Regensburg University, the German-born Pope explored the historical and philosophical differences between Islam and Christianity, and the relationship between violence and faith.

The remarks do not express correct understanding of Islam

Mohammed Mahdi AkefMuslim Brotherhood

Stressing that they were not his own words, he quoted Emperor Manual II Paleologos of the Byzantine Empire, the Orthodox Christian empire which had its capital in what is now the Turkish city of Istanbul.

The emperor's words were, he said: "Show me just what Muhammad brought that was new and there you will find things only evil and inhuman, such as his command to spread by the sword the faith he preached."

Benedict said "I quote" twice to stress the words were not his and added that violence was "incompatible with the nature of God and the nature of the soul".

'Angry and hurt'

Pakistan's parliament passed a resolution demanding that the Pope retract his remarks "in the interest of harmony between religions".

"The derogatory remarks of the Pope about the philosophy of jihad and Prophet Mohammed have injured sentiments across the Muslim world and pose the danger of spreading acrimony among the religions," the AFP news agency quoted the resolution by the country's national assembly as saying.

Meanwhile, the "hostile" remarks drew a demand for an apology from a top religious official in Turkey - where the Pope is due in November on his first papal visit to a Muslim country.

Ali Bardakoglu recalled atrocities committed by Roman Catholic Crusaders against Orthodox Christians and Jews, as well as Muslims, in the Middle Ages.

In Egypt, Muslim Brotherhood head Mohammed Mahdi Akef said the Pope's words "do not express correct understanding of Islam and are merely wrong and distorted beliefs being repeated in the West".

In a statement, he was "astonished that such remarks come from someone who sits on top of the Catholic church which has its influence on the public opinion in the West".

Sheikh Youssef al-Qardawi, a prominent Muslim cleric in Qatar, rejected the Pope's comments, in remarks reported by Reuters.

"Muslims have the right to be angry and hurt by these comments from the highest cleric in Christianity," Mr Qardawi reportedly said.

"We ask the Pope to apologise to the Muslim nation for insulting its religion, its Prophet and its beliefs."

The 57-nation Organisation of the Islamic Conference also said it regretted the Pope's remarks, and news agencies reported a furious reaction on Islamic websites

Thursday, September 14, 2006

US Image in the world

I think the poll below reflects the general attitude in Indonesia toward American policies in Middle East Conflict, and the attitudes is actually not permanent, depending on how American government deal with the conflict; if the Indonesians see that the U.S. show a double standard, or support Israel, not the other side, then Indonesians would think that the U.S. does badly in their goodwill to solving the conflict. Not many Indonesians know very well of American diversity regarding Middle East problems; what they know is that if Israeli-Palestinian conflict is not resolved peacefully and justly, Iraq conflict is not dealt effectively and quickly, then they put the blame on the U.S. because they see how the U.S. had intervered.

The perception gap between the US and the Muslim world is still wide, and everyone should take part in bridging it.

M.Ali

Poll finds distrust of U.S. over Lebanon

Abdul Khalik, The Jakarta Post, Jakarta

A majority of Indonesians believe the United States was directly or indirectly involved in the recent conflict in Lebanon, according to a survey by a global polling group.

The poll by Gallup International Association, which groups market research companies in some 60 countries, involved 403 Jakartans from across the economic spectrum.

Seventy-three percent of respondents believed the U.S. was involved in the war. Only 3 percent thought Iran or Islamic extremists had something to do with the conflict, according to the poll results released Wednesday.

Globally, only a third of all people surveyed thought the U.S. was involved in the conflict in Lebanon.

The poll, conducted between Aug. 11-13, was part of a survey of almost 25,000 respondents in 33 countries to determine global opinion on the war in Lebanon.

Of the Indonesian respondents, 85 percent thought Israel had gone too far in its military action.

"Opinions are clear as to who initiated the conflict," a report on the poll results said. "In 24 countries included in the survey, more people mention Israel than Hizbollah. Of those interviewed in Indonesia, four out of five echoed this same opinion."

"The results are predictable," Hariyadi Wirawan, an international relations expert, told The Jakarta Post on Wednesday.

"The poll results are just an accumulation of anti-American sentiment here, resulting from U.S. support for Israel in Lebanon and Palestine."

He said the negative views of the U.S. were reinforced by a recent visit to Indonesian by Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, who is admired here for his fiery rhetoric.

"Whatever the facts, most Indonesians will think that it was all the work of the U.S. Worse, when it comes to Israel, the U.S. doesn't care to improve its image," Hariyadi said.

Around 1,100 people in Lebanon and 156 Israelis died in the conflict, which began after Hizbollah captured two Israeli soldiers in a cross-border raid on July 12. Only after the UN Security Council issued Resolution 1701, which took effect in mid-August, did the 34-day conflict end.

The United Nations is trying to assemble a multinational force of 15,000 soldiers to help keep the peace in southern Lebanon. Indonesia will send some 850 soldiers to Lebanon by the end of this month as part of the peacekeeping force.

Ninety-six percent of Indonesian respondents in the poll agreed the country should send peacekeeping troops to Lebanon.

Globally, the majority of respondents believe there can be no peace in the region without the settlement of the Israel-Palestine issue, and that the U.S. should not interfere in the conflict. These two sentiments were echoed by those interviewed in Indonesia, the poll report said.

Some 95 percent of Indonesian respondents were also of the opinion that the war in Israel and Lebanon would likely expand and come to involve other countries.

The perception gap between the US and the Muslim world is still wide, and everyone should take part in bridging it.

M.Ali

Poll finds distrust of U.S. over Lebanon

Abdul Khalik, The Jakarta Post, Jakarta

A majority of Indonesians believe the United States was directly or indirectly involved in the recent conflict in Lebanon, according to a survey by a global polling group.

The poll by Gallup International Association, which groups market research companies in some 60 countries, involved 403 Jakartans from across the economic spectrum.

Seventy-three percent of respondents believed the U.S. was involved in the war. Only 3 percent thought Iran or Islamic extremists had something to do with the conflict, according to the poll results released Wednesday.

Globally, only a third of all people surveyed thought the U.S. was involved in the conflict in Lebanon.

The poll, conducted between Aug. 11-13, was part of a survey of almost 25,000 respondents in 33 countries to determine global opinion on the war in Lebanon.

Of the Indonesian respondents, 85 percent thought Israel had gone too far in its military action.

"Opinions are clear as to who initiated the conflict," a report on the poll results said. "In 24 countries included in the survey, more people mention Israel than Hizbollah. Of those interviewed in Indonesia, four out of five echoed this same opinion."

"The results are predictable," Hariyadi Wirawan, an international relations expert, told The Jakarta Post on Wednesday.

"The poll results are just an accumulation of anti-American sentiment here, resulting from U.S. support for Israel in Lebanon and Palestine."

He said the negative views of the U.S. were reinforced by a recent visit to Indonesian by Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, who is admired here for his fiery rhetoric.

"Whatever the facts, most Indonesians will think that it was all the work of the U.S. Worse, when it comes to Israel, the U.S. doesn't care to improve its image," Hariyadi said.

Around 1,100 people in Lebanon and 156 Israelis died in the conflict, which began after Hizbollah captured two Israeli soldiers in a cross-border raid on July 12. Only after the UN Security Council issued Resolution 1701, which took effect in mid-August, did the 34-day conflict end.

The United Nations is trying to assemble a multinational force of 15,000 soldiers to help keep the peace in southern Lebanon. Indonesia will send some 850 soldiers to Lebanon by the end of this month as part of the peacekeeping force.

Ninety-six percent of Indonesian respondents in the poll agreed the country should send peacekeeping troops to Lebanon.

Globally, the majority of respondents believe there can be no peace in the region without the settlement of the Israel-Palestine issue, and that the U.S. should not interfere in the conflict. These two sentiments were echoed by those interviewed in Indonesia, the poll report said.

Some 95 percent of Indonesian respondents were also of the opinion that the war in Israel and Lebanon would likely expand and come to involve other countries.

Tuesday, September 12, 2006

The epithet Islamic Fascism is Unhelpful

Why the epithet 'Islamic fascism' is unhelpful to search for peace

Muhamad Ali, The Jakarta Post, September 13, 2006

President George W. Bush's epithet "Islamic fascists" in talking about the arrest of the suspected terrorists in London and about Hizbollah and Hamas and the popularization of the epithet by other politicians associating a particular strand of Islamic ideology with "a new type of fascism" does more harm than good in our attempt at bridging the perception gap between the Muslim world and the West.

These buzzwords and excessive jargon, especially among American fundamentalists, have shifted us from identifying and solving the real problems and the root causes of transnational terrorism, the enemy of all world citizens.

There are some reasons why the labeling of a group of terrorists as Islamic fascists is unhelpful in our peace-making and peace-building efforts.

First, "Islamic fascism" is more a fanciful invention than an explanation of fact and historical truth. Of course President George W. Bush and others using the term do not feel the need to explain their definition and do not care about how this term might insult the Muslim majority, because for Bush and others it has becomes clear that terrorists fight against freedom and democracy. The terrorists do not use the word fascism and most moderates do not view them as such. Fascism which emerged in Italy was then used very loosely to mean all manner of things.

Second, it will incite the Muslim radicals to use more buzzwords. The term Islamic fascism can be misused by the radicals and the terrorists themselves in their counterattack. In world history, the use of buzzwords during wars is common among conflicting parties, Today there are the same buzzwords used to demonize the West, America, Jewish people and Israel, such as the "infidels", etc.

For example, in an Iranian newspaper, Bush is depicted as "the 21st century Hitler" and Tony Blair as "the 21st century Mussolini". Certainly Bush and Blair do not like to be called that.

It is thus the task of the leaders and moderate groups everywhere to moderate the extremists on both sides of the conflict. Demonization creates further demonization, and violence comes very easily from and with this. But for the 21st century generation of peacetime leaders they must stop using terms and jargon that are not in conformity with facts and realities.

Third, the moderates feel uneasy and uncomfortable about the attachment of the term fascism to the peaceful religion of Islam since fascism has been commonly used in a derogatory and negative manner. It will become harder for the moderates and liberals to bridge the gap between themselves and the radicals when they learn how Western leaders make fun of Islam by attaching extremist words to the religion.

For the moderates, terrorism, or fascism, is alien to Islam, and this should be borne in mind. When al-Qaeda uses Islam for its violent acts the moderates can easily say "that is not our Islam" and the later can work to discount their theology of violence.

But when the outsiders or the enemies of the terrorists label the terrorist group with Islamic fascism, the moderates cannot say "that Islamic fascism is not our Islam" because the terrorist themselves do not use the term nor do they show a full conformity with the characteristics of fascism.

Fourth, when Islam is attached to an extreme ideology, it may imply that Islam plays a part in the creation of such extremist ideologies. All scriptures, the Old Testament, New Testament, Veda, and the Koran can be interpreted to legitimize any strand of political ideology, but the majority of religious believers would not accept their interpretation of religious scriptures.

The feeling of the majority will not be different when for example Christianity or Judaism is associated with fascism by some. The same feeling will also arise when for example terrorism is associated with Americans -- "American terrorism", as many people in Iraq, Afghanistan, or Vietnam, describe it.

Therefore, labeling is always simplistic, but can become unhelpful and dangerous when the majority, whether they be Muslims, Americans or Westerners etc., do no share certain derogatory epithets.

If they want to refer to group of terrorists, they may name them, such as al-Qaeda, Jamaah Islamiyah, Islamic Jihad, HAMAS, Hizbollah, etc. instead of using the word Islamic for any ideology emerging from the Muslim tradition and history without a clear definition and full understanding of the characteristics and diversity of Muslim movements.

To quote French philosopher Claude Levi-Strauss: "Words are instruments that people are free to adapt to any use, provided they make clear their intentions." Categorization becomes useful and helpful if it clarifies what one is trying to say in order to facilitate communication and understanding.

The war today seems to be waged by fundamentalists on both sides, both Western fundamentalists and Muslim fundamentalists. Extremism and the use of violence have emerged from sectors of the Western peoples, as well as from the part of the Muslim world.

We may say this is the clash of fundamentalism, and in most cases, a clash of ignorance, since neither sides wishes to moderate their attitude. They fight against each other on behalf of God and in the name of God. And God might well be laughing watching His people fighting against each other, killing civilians, and destroyed civilizations in His name and in His service.

It is a difficult task for moderates and liberals in the Muslim world to explain to the Muslim audience why American leaders keep using such buzzwords as Islamic fascism to refer to a handful of terrorist groups. Why is it so easy for non-Muslim westerners to associate the noble and sacred term Islam with such a popularly perceived enemy as fascism?

Both sides, Western governments and the terrorists, have to understand the limits of their powers if peace is to be achieved. If they continue to be preachers of hate and actors of war peace will never materialize. What we need now is not to appease both Western arrogance and to appease the terrorist groups.

What we need today are "boundary leaders" who are honestly and seriously willing to transcend their own way of seeing things, to understand why they hate us as well as why we hate them, and to find pragmatic ways to solve the root causes, not by perpetuating the long-existing gaps. What we need now are convincing speeches that try to talk to and to convince as many people as possible to pursue world peace

Muhamad Ali, The Jakarta Post, September 13, 2006

President George W. Bush's epithet "Islamic fascists" in talking about the arrest of the suspected terrorists in London and about Hizbollah and Hamas and the popularization of the epithet by other politicians associating a particular strand of Islamic ideology with "a new type of fascism" does more harm than good in our attempt at bridging the perception gap between the Muslim world and the West.

These buzzwords and excessive jargon, especially among American fundamentalists, have shifted us from identifying and solving the real problems and the root causes of transnational terrorism, the enemy of all world citizens.

There are some reasons why the labeling of a group of terrorists as Islamic fascists is unhelpful in our peace-making and peace-building efforts.

First, "Islamic fascism" is more a fanciful invention than an explanation of fact and historical truth. Of course President George W. Bush and others using the term do not feel the need to explain their definition and do not care about how this term might insult the Muslim majority, because for Bush and others it has becomes clear that terrorists fight against freedom and democracy. The terrorists do not use the word fascism and most moderates do not view them as such. Fascism which emerged in Italy was then used very loosely to mean all manner of things.

Second, it will incite the Muslim radicals to use more buzzwords. The term Islamic fascism can be misused by the radicals and the terrorists themselves in their counterattack. In world history, the use of buzzwords during wars is common among conflicting parties, Today there are the same buzzwords used to demonize the West, America, Jewish people and Israel, such as the "infidels", etc.

For example, in an Iranian newspaper, Bush is depicted as "the 21st century Hitler" and Tony Blair as "the 21st century Mussolini". Certainly Bush and Blair do not like to be called that.

It is thus the task of the leaders and moderate groups everywhere to moderate the extremists on both sides of the conflict. Demonization creates further demonization, and violence comes very easily from and with this. But for the 21st century generation of peacetime leaders they must stop using terms and jargon that are not in conformity with facts and realities.

Third, the moderates feel uneasy and uncomfortable about the attachment of the term fascism to the peaceful religion of Islam since fascism has been commonly used in a derogatory and negative manner. It will become harder for the moderates and liberals to bridge the gap between themselves and the radicals when they learn how Western leaders make fun of Islam by attaching extremist words to the religion.

For the moderates, terrorism, or fascism, is alien to Islam, and this should be borne in mind. When al-Qaeda uses Islam for its violent acts the moderates can easily say "that is not our Islam" and the later can work to discount their theology of violence.

But when the outsiders or the enemies of the terrorists label the terrorist group with Islamic fascism, the moderates cannot say "that Islamic fascism is not our Islam" because the terrorist themselves do not use the term nor do they show a full conformity with the characteristics of fascism.

Fourth, when Islam is attached to an extreme ideology, it may imply that Islam plays a part in the creation of such extremist ideologies. All scriptures, the Old Testament, New Testament, Veda, and the Koran can be interpreted to legitimize any strand of political ideology, but the majority of religious believers would not accept their interpretation of religious scriptures.

The feeling of the majority will not be different when for example Christianity or Judaism is associated with fascism by some. The same feeling will also arise when for example terrorism is associated with Americans -- "American terrorism", as many people in Iraq, Afghanistan, or Vietnam, describe it.

Therefore, labeling is always simplistic, but can become unhelpful and dangerous when the majority, whether they be Muslims, Americans or Westerners etc., do no share certain derogatory epithets.

If they want to refer to group of terrorists, they may name them, such as al-Qaeda, Jamaah Islamiyah, Islamic Jihad, HAMAS, Hizbollah, etc. instead of using the word Islamic for any ideology emerging from the Muslim tradition and history without a clear definition and full understanding of the characteristics and diversity of Muslim movements.

To quote French philosopher Claude Levi-Strauss: "Words are instruments that people are free to adapt to any use, provided they make clear their intentions." Categorization becomes useful and helpful if it clarifies what one is trying to say in order to facilitate communication and understanding.

The war today seems to be waged by fundamentalists on both sides, both Western fundamentalists and Muslim fundamentalists. Extremism and the use of violence have emerged from sectors of the Western peoples, as well as from the part of the Muslim world.

We may say this is the clash of fundamentalism, and in most cases, a clash of ignorance, since neither sides wishes to moderate their attitude. They fight against each other on behalf of God and in the name of God. And God might well be laughing watching His people fighting against each other, killing civilians, and destroyed civilizations in His name and in His service.

It is a difficult task for moderates and liberals in the Muslim world to explain to the Muslim audience why American leaders keep using such buzzwords as Islamic fascism to refer to a handful of terrorist groups. Why is it so easy for non-Muslim westerners to associate the noble and sacred term Islam with such a popularly perceived enemy as fascism?

Both sides, Western governments and the terrorists, have to understand the limits of their powers if peace is to be achieved. If they continue to be preachers of hate and actors of war peace will never materialize. What we need now is not to appease both Western arrogance and to appease the terrorist groups.

What we need today are "boundary leaders" who are honestly and seriously willing to transcend their own way of seeing things, to understand why they hate us as well as why we hate them, and to find pragmatic ways to solve the root causes, not by perpetuating the long-existing gaps. What we need now are convincing speeches that try to talk to and to convince as many people as possible to pursue world peace

With Azyumardi Azra in Hawaii September 2006

Bersama Prof Azyumardi Azra di Hawaii, yang diundang Seminar tentang Pendidikan Tinggi sebagai Milik Publik dan Privatisasi di East-West Center, saya mendapat banyak pengetahuan dan pengalaman yang dishare secara santai dan terus terang. Semoga kebersamaan ini menambah motivasi saya untuk terus mengembangkan ilmu dan integritas kepribadiaan yang amat mahal itu. I hope that exchange of views and experiences with Pak Azra helps me strengthen my dedication to knowledge and its development in the future for the benefit of humankind and the universe.

Belajar dari Kak Edy

Oleh: Muhamad Ali

Kak Edy, begitulah kolega yunior biasa memanggilnya. Sebagian memanggilnya Pak Azyumardi, dan orang di luar negeri Prof. atau Dr. Azra. Kami, mahasiswa dan dosen muda yang sedang studi di luar negeri, terus belajar banyak dari kiprah Kak Edy sebagai cendekiawan Muslim yang diakui dalam bidangnya, sejarah, dan kajian-kajian Islam, juga sebagai duta Islam di dunia Barat, dan sebagai manajer perguruan tinggi yang berhasil.

Cendekiawan Muslim

Dalam sebuah kesempatan, Prof Nurcholish Madjid (almarhum) memuji Kak Edy sebagai rektor dan cendekiawan yang paling sering dimintai pendapat-pendapatnya mengenai berbagai isu sosial keagamaan dan politik. Sebagai cendekiawan Muslim, Kak Edy punya wawasan luas, menerawang ke banyak sisi yang sering luput dari pengamatan banyak orang.

Dengan koleksi perpustakaan pribadi sekitar 20 ribuan saat ini, buku memang jadi teman dekatnya. Kak Edy sangat mencintai buku. Anak-anaknya ketika ulang tahun diajak ke toko buku dan disilahkan membeli buku. Bahkan untuk kemudahan akses, sudah ada on-line library sehingga kalangan akademik dan masyarakat bisa memanfaatkannya. Kak Edy sangat produktif menulis. “Saya menulis sebelum dan sesudah Subuh, karena inilah waktu yang terbaik buat saya”, dan karena itu saya berusaha tidur tidak terlalu malam.” Di manapun pergi dia coba membaca dan menulis. Kesibukan sebagai pejabat tidak membuatnya enggan menuangkan pikiran-pikirannya.

Banyak mahasiswa dan dosen muda yang meminta surat rekomendasinya untuk bisa mendapatkan beasiswa studi di luar negeri. Berpuluh-puluh, bahkan mungkin ratusan penulis, baik politisi maupun akademisi, memintanya untuk menulis kata pengantar buku-buku mereka dari berbagai disiplin ilmu. Ada kepuasan intelektual ketika penulis mendapatkan pengakuan Azyumardi Azra lewat kata pengantarnya.

Duta Islam di Barat

Seperti Ketua Umum Muhammadiyah sekarang Prof M. Dien Syamsuddin, dan Ketua PB Nahdlatul Ulama, KH Hasyim Muzadi, peranan kak Edy sebagai juru bicara Muslim Indonesia sudah dikenal dunia. Karena kemampuannya membaca sejarah dan peristiwa kontemporer, banyak cendekiawan dan diplomat di Amerika Serikat (AS) dan di Negara-negara lain memuji. Contohnya, seorang pengamat politik asal AS pernah menulis, “Pak Azra selalu memberi nilai tambah dalam setiap pertemuan mengenai Islam.” Seorang yang lain mengatakan, “Kami sangat berterima kasih atas kesediaan Pak Azra mengikuti konferensi ini.” Dan seorang profesor pernah berkata, “He is very knowledgeable and smart”.

Dalam konferensi dan tulisannya, Kak Edy menekankan bahwa Islam di Indonesia itu moderat dan anti kekerasan apalagi terorisme. Media dan pemerintah Barat masih banyak yang tidak paham ajaran Islam yang mencintai perdamaian, dan tidak paham bahwa mayoritas Muslim di dunia, terutama di Asia Tenggara, adalah moderat. Karena itu kerjasama internasional, dari berbagai agama dan ideologi politik, sangat diperlukan untuk dapat memenangkan perang melawan terorisme itu.

Kak Edy berusaha berpikir dan berpendapat obyektif sesuai dengan wawasannya. Dia berkata, “Janganlah anti Amerika secara membabi buta; kita harus kritis terhadap Amerika secara obyektif, terhadap kebijakan-kebijakan pemerintahnya yang membahayakan, tapi kita juga perlu menghargai peran Amerika dalam pendidikan dan kerjasama-kerjasama dalam berbagai bidang.”

Pak Azra adalah sosok dengan jaringan akademik dan pemerintahan yang luas. Dengan jaringan itulah, kerjasama-kerjasama pendidikan bisa lebih mungkin. Kepemimpinan terasing dan eksklusif tidak akan membantu perkembangan lembaga pendidikan tinggi. Kerjasama bisa terbuka, tidak hanya dengan Amerika Serikat, tapi juga Iran, bahkan Rusia, Cina, Timur Tengah, dan sebagainya, sejauh bertujuan mengembangkan ilmu pengetahuan.

Ketika ditanya mengapa sering ke luar negeri, Kak Edy menjawab hal itu demi pencitraan Islam Indonesia atau Asia Tenggara, Indonesia yang majemuk dan moderat, sekaligus memajukan institusi universitas yang dipimpinnya. “Datang saja ke kampus di Ciputat”, begitu jawabnya ketika orang mempertanyakan kenapa sebagai rektor dia sering ke luar negeri. “Saya tidak suka jalan-jalan, ketika diundang ke seminar-seminar ke berbagai Negara, paling-paling saya berada di tempat konferensi dan hotel tempat menginap. Saya menggunakan uang dinas untuk kepentingan dinas, dan tidak mau menggunakan uang dinas untuk kepentingan jalan-jalan, tinggal di hotel mewah, belanja, dan seterusnya. Saya menyempatkan ke toko buku.”

Manajer Perguruan Tinggi

Kerjasama-kerjasama internasional dibawah Pak Azra memang fenomenal, dari banyak pemerintah dan lembaga-lembaga swasta. Fakultas Kedokteran misalnya mendapat bantuan dana dari sebuah lembaga Jepang. Bahkan Library of Congress siap membantu perpustakaan kampus Universitas Jakarta. Seorang sejarawan Merle Ricklefs misalnya sudah berwasiat akan memberikan seluruh bukunya jika wafat nanti ke perpustakaan UIN Jakarta.

Terhadap para karyawan di kampus Pak Azra punya perhatian besar. “Jangan kita menuntut satpam untuk bekerja keras tapi gajinya sangat tidak manusiawi.” Dia merasakan korupsi sistemik di kalangan pejabat di departemen-departemen, disebabkan banyak faktor selain lemahnya penegakkan hukum, adalah gaji yang tidak layak. Korupsi para pejabat, politisi, dan masyarakat sudah akut, sehingga tugas pemberantasan korupsi juga harus melibatkan para moralis dan agamawan yang bergerak secara subtantif, dan bukan sekedar formalistik ritualistik.

Kak Edy telah berhasil mentransformasi institut yang awalnya hanya ilmu-ilmu agama konvensional menjadi Universitas Islam Negerti (UIN) yang berusaha mengintegrasi ilmu-ilmu agama dan ilmu-ilmu umum, sesuai yang dimandatkan, dan menbangun sistem pendidikan tinggi yang lebih baik, UIN menjadi universitas riset internasional di masa depa. Dengan keterbatasan yang masih ada, terutama sumber daya manusia pengajar dan karyawan, Kak Edy berharap UIN mampu mengejar ketinggalan dan berkompetisi dengan universitas-universitas lain yang lebih dahulu mapan.

Setelah rektor nanti, Kak Edy akan tetap berkiprah, akan terus membaca, menulis, dan memberikan sumbangan pemikiran bagi kemaslahatan umat dan bangsa. Kami belajar banyak dari Kak Edy, seperti dari banyak tokoh lainnya yang telah dan terus berjasa bagi pencerahan kehidupan bangsa. Bangsa ini butuh lebih banyak lagi cendekiawan pemimpin yang berdedikasi pada pengembangan ilmu pengetahuan dan keterlibatan aktif membantu bangsa ini keluar dari krisis multidimensi.

Sunday, September 10, 2006

survey U.S Image

Survey: U.S Image Deteriorates in Asia

The Jakarta Post, September 10, 2006

TOKYO (AP): The image of the United States has deteriorated across Asia in recent years, particularly in countries with large Muslim populations, according to a survey published in a Japanese newspaper Sunday.

The seven-nation survey, jointly conducted by the Yomiuri Shimbun newspaper, the Korea Times and the Gallup group, showed the proportion of respondents with a positive view of the U.S. image dropped in all countries from the last poll in 1995.

Positive views about the U.S. outnumbered negative ones overall, but more people said their opinion of the United States had diminished, the Yomiuri said.

"The proportion of respondents who said their perception of the United States was good slipped, and those giving negative responses increased in most of the countries compared with the results of a 1995 survey," the newspaper said.

The seven countries surveyed were Japan, India,Indonesia, Malaysia, South Korea, Thailand and Vietnam. The survey did not ask respondents why their views of the U.S. had diminished.

The rise of anti-U.S. sentiment was most evident in predominantly Muslim Malaysia, where respondents with negative views of the U.S. surged 30 percentage points to 41 percent.

In Indonesia, the world's most populous Islamic nation, the percentage of negative responses jumped 16 points to 40 percent.

In South Korea, the percentage of negative respondents increased 14 percentage points to 48 percent, while in Japan, a staunch U.S. ally, negative responses rose 7 points to 25 percent.

But in India, where the question was not asked in the 1995 survey, 83 percent said their image of the U.S. was good and only 15 percent said it was bad.

In Thailand, 74 percent of respondents said the U.S. was good, while 88.6 percent of Vietnamese queried gave positive answers.

Comparisons to the 1995 survey weren't given for the two Southeast Asian nations.

More than 1,000 people were interviewed in June and July in each of the seven countries. No margin of error was provided. (***) -->

Thursday, August 31, 2006

Tolerant Nationalism

Promoting tolerant nationalism, beyond religious versus secular

Muhamad Ali, Manoa, Hawaii

The commemoration of Independence Day every Aug. 17 may leave certain crucial questions unanswered, despite all the underlying spirit, surrounding symbols and colorful celebrations. One such question is whether Indonesian nationalism was and continues to be secular or religious.

Scholars have attempted to provide answers to this delicate and complex question, but most of them are trapped in a dichotomous opposition between the religious and the secular. In fact, for many Indonesian Muslims, Christians, Buddhists, Hindus and Confucians, nationalism is both secular and religious. Pancasila has become the ambiguous yet accepted ideology of Indonesia's nationalism. But what can we, as a nation, gain from it?

Most Western literature on Indonesian nationalism argues that historically the emergence of nationalism was attributed to the rise of secular leaders such as Sukarno and Hatta (both being graduates of the Dutch educational system) and a secular print media, including Budi Utomo and the Indonesian National Party of Sukarno. Nationalism is believed to be a Western import, and it was secularly educated leaders who introduced this concept to this new country.

This argument has been challenged by many. Michael Francis Laffan, in his Islamic Nationalism and Colonial Indonesia (2003), argues that Islam played a crucial role in the rise of Indonesian nationalism. According to him, it was Muslim scholars and leaders, influenced by Islamic reform movements in Mecca-Medina and then Egypt, through their religious organizations (such as Syarikat Islam, Nahdlatul Ulama and Muhammadiyah), publications and activism, who worked in anti-colonial movements during the early 20th century. These two arguments stand upon their own emphasis of certain movements and individuals in selected moments of history.

The essence of nationalism is patriotism, or love of the native land. This love of the native land has very constructive impacts on the life of a nation. By this spirit of love, all members of a nation are willing to work hard to build their country into a prosperous and peaceful one. Also by this spirit, self-determination arises and can become a strong force in self-improvement and nation-building.

In interfaith meetings, every religion attempts to argue that nationalism and patriotism are sanctioned by their religious beliefs, and their gods teach them to love their country and to work hard for it. This may be called religious nationalism, for the absence of a better term, to suggest that nationalism and religion are not incompatible in the heart and minds of many of these religious peoples.

If one says nationalism was and is Islamic, then a question may arise: Were there only Muslims who fought against colonialism? They were a majority certainly in the struggle against colonialism, but were there Protestants, Catholics, Hindus, Buddhists, Confucians and non-religious peoples in nationalist movements?

This question leads to the very problem Indonesia has faced again and again: Is Indonesia truly a pluralistic nation? To the latter question, many Islamic political parties and leaders have only one answer: that it was Muslims who played the main role in gaining and keeping independence and therefore it is the Muslims' right to determine the direction of the nation by their particularistic laws.

It is often claimed that Muslims gave up seven words of the Jakarta Charter (with the obligation for Muslims to observe their religious beliefs) and presented it to non-Muslims of the nation as a gift. For them, Pancasila was often seen as a gift to the pluralistic nation, compromising Islamic ambitions to make the nation-state an Islamic state.

Thus it is hardly present in the minds of the Muslim majority that Protestants, Hindus, Buddhists, Confucians and others, whether or not they identified themselves as such, participated in the struggle against colonialism, and have long contributed to the development of the nation.

Pre-independence nationalism was to get rid of the Japanese and the Dutch, but post-independence nationalism was to contribute to the development of the country in all aspects of life. Some post-independence nationalists argue that nationalism should today mean anti-neoimperialism, economic imperialism in the form of capitalism (and its representative institutions) and so forth.

More recently, some Nahdlatul Ulama leaders issued a manifesto that criticizes new modes of imperialism in the form of external forces imperializing Indonesia economically, politically, culturally and intellectually. This neo-nationalism is sometimes linked to particular religious interpretations as well.

How should we resolve this question? There is no one answer to this. Nationalism is perhaps neutral in itself. It is a good thing to love one's country. Every community in the world today, including the Muslim world, has accepted nationalism as the best political ideology.

But we are facing excesses of nationalism: Aggressive nationalism which tries to impose one's nationalism onto other nations near and far. Between nations, tolerant nationalism, either religious or secular, should be promoted.

Indonesian nationalism, either religiously or secularly based, can have excesses and extremes as well. Extreme nationalism, for example, forces minorities to adopt the overarching political agenda that they would otherwise reject because it does not suit their needs and interests.

An extreme nationalism wants to civilize the margins (indigenous believers, religious sects, new religious movements, mountain and jungle tribes, and so forth) by way of imposition without respect for their particular conditions and needs. Within a nation, there needs to be a balance between nationalism and multiculturalism.

Thus, we should now go beyond secular versus religious nationalism. It is time to promote more substantive and tolerant nationalism: strong, solid, but respecting other concepts of nationalism and nationalities within and without the country. Tolerant nationalism is a love of one's country manifested in various aspects of life, but not at the expense of the destruction of other peoples within and beyond the constructed boundaries.

Indonesian nationalism should be tolerant in the sense that, whether religious or secular or mixed according to different communities, it should respect minorities and the marginal, and at the same time should respect other nationalisms outside it. One of the outcomes of such tolerant nationalism is continued participation within the nation and peaceful coexistence and fruitful cooperation outside it.

Photo: Me, my Professor Jerry Bentley, and classmatess at World History class, Hawaii, 2004.

Wednesday, August 30, 2006

DEFINING PLURALISM IN CONTEXT

By Muhamad Ali

A paper for discussion at the Center for the Languages and Cultures, UIN Jakarta, April 2005

Pluralism still needs further and wider discussion among various elements in Indonesia, not only because of its condemnation by the Council of Indonesian Ulema, of the condemnation and attacks against the marginalized movement of Ahmadiyah, and of the forced closure of over 200 churches by the Islam Defender’s Front (FPI) since 1996 to date, but also because of the complexity and changes of its very term in the intellectual history of modern societies. Franz Magnis-Suseno’s article “Defining Pluralism, Liberalism, Secularism” has been particularly insightful in stressing the value of pluralism and its difference from relativism, but it will be useful to understand that the vocabulary of pluralism has changed and differed according to time and space.

It is true that we do not have to agree in what pluralism means and it never has one monolithic denotation. “Words”, says French philosopher Claude Levi-Strauss, “are instruments that people are free to adapt to any use, provided they make clear their intentions.” In the social sciences, as in philosophy and religion, there are wide and frequent variations in the meaning of the simplest words, according to the thought that uses and informs them.

The use of the state or the religious authority to enforce particular understanding of religion is one thing, but the disagreement on the meaning of the terms (such as pluralism) is another thing, which we should scrutinize further.

The forced closure of 23 churches in Bandung between September 2004 and August 2005 by the Islam Defender’s Front (FPI), and over 200 churches since 1996 raises questions: to what extent can churches be regarded as harming the Muslim environment or social order? Does one religious community have the right to convert other religious communities and what should the government do about this? Can we tolerate the intolerant groups like FPI?

Pluralism means differently and dynamically. In one definition, it is diversity that denotes a fact, a condition, a reality of difference, while pluralism is an ideal or impulse, the acceptance and encouragement of diversity. In another, pluralism is a state of society in which members of diverse ethnic, racial, religious, or social groups maintain an autonomous participation in and development of their traditional culture or special interest within the confines of a common civilization. It can also be defined as a concept, doctrine, or policy advocating this state. Thus, Pluralism is defined not as diversity itself but as one of the various things people do and think in response to diversity (Wesbter’s Third International). This notion of pluralism did not emerge until the 1920s.

Pluralism can be seen from different levels: first, pluralism as toleration (absence of persecution, the right of a deviant to exist), pluralism as inclusion (to include outsiders, but not yet equal), and pluralism as participation (a mandate for individuals and groups to share responsibility for the forming and implementing of the society’s agenda. (William R. Hutchison, Religious Pluralism in America, 2003)

In the political context, pluralism is the belief in the distribution of political power through several institutions which can limit one another’s action, or through institutions none of which is sovereign. Pluralism is the advocacy of a particular kind of limited government. Second, pluralism is the belief that the constitution of a state ought to make room for varieties of social customs, religious, and moral beliefs, and habits of association, and that all political rights should be traced back to the constitution, and not to any social entity other than the state itself. In such circumstances the social and the political are as separate as can be, and uniform political institutions coexist with a plural society (a civil society in which several societies coexist in a single territory, interacting in a peaceful way, perhaps so as to become socially, politically, and economically interdependent). And third, pluralism is any view which, in opposition to monism (and to dualism), argues for a multiplicity of basic things, processes, concepts or explanations. (Roger Scruton, A Dictionary of Political Thought, 1996)

Pluralism, Religious Pluralism, Multiculturalism As Practices and Concepts

During the 18th century: French and German Enlightenment and Particular Meaning of Pluralism: liberalism, against absolutism of the Church, Jean-Jacques Rousseau (Social Contract, Civil Religion)

In the U.S., diversity happened to American religion in the first half of the 19th century, but pluralism as a concept did not arrive until the second half of the 20th century.

During the 19th century: pluralism as toleration; Protestant dominance continued; peoples were “in harmony and good neighborhood, no disputes about religion, nearly complete absence of polemical strife and bitterness in the religious life” (Crèvecouer) “the Christian, the infidel, the Mohammadan, the Jew, the Deist, has not only all his right as a citizen, but many have his own form of worship, without the possibility of any interference from any policeman or magistrate, provided he do not interrupt, in so doing, the peace and tranquility of the surrounding neighborhood” (Robert Baird, 1840s) “if you were a cultural outsider, you could be about as different as you wished in actual religious views. And it meant that if you were an outsider, acceptance depended to a large extent upon your willingness to adjust, to become assimilated, especially in matters of religious and general behavior.” “in the U.S, Christian sects are infinitely diversified and perpetually modified; but Christianity itself is an established and irresistible fact.” (Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, 1834-40).

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries: pluralism as inclusion; nonmainstream sectarians, Catholics, Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, Hindus, to be recognized and included as part of the society (given a voice, but not beyond that), Reform Judaism and Inclusionary Pluralism: “We recognize in every religion an attempt to grasp the Infinite One”, Liberal Catholics and the Quest for Inclusion, the World’s Parliament of Religions (1893) as a showcase for inclusion.

Mid-20th century: New Mainstream, New Pluralism, Pluralism as participation: Protestant establishment of old was sharing its mainstream status with the other two major faiths (Catholics and Judaism). Islam nearly matched Judaism (6 millions in size)

Contemporary America: Whose America? A. Samuel Huntington “Who are We: The Challenges to American National Identity” (2004), reasserts Protestant roots of America. The challenges to American identity are subnational identities, immigrants, assimilations, militant Islam. B. Willaim Hutchison’s Religious Pluralism: “We should accept pluralism as a primary value, but that we must also deal seriously with pleas concerning social and moral cohesion.”, beyond inclusion, that is mutually respectful and nonpatronizing.” One still hold to his or her own convictions, does not mean lack of all conviction. Not to say we are chosen and you are not “ “.voluntary, mono or multiple identities.” Renewed civil religion. “Recognition by both religious and nonreligious peoples that the days are past when any one group can dictate a comprehensive public philosophy that will prevail for the whole of the people (Prof. Marsden, 1990), Civil Religion (Robert Bellah, 1970s) Thus, Religious Pluralism as a Work in Progress in the U.S.: advanced pluralist thinking has now gone beyond mere toleration and mere inclusion, although intolerance and exclusion persist. (Hutchison, 2003) Some regard pluralism as dangerous loss of consensus and social cohesion, but Hutchison sees pluralism and social cohesion can coexist

Religious Pluralism: Some Definitions

“All religions are the relative- that is, limited, partial, incomplete, one way of looking at thing. To hold that any religion is intrinsically better than another is felt to be somehow wrong, offensive, narrow-minded; Deep down , all religions are the same – different paths leading to the same goal.” (Paul Knitter, No Other Name? A Critical Survey of Christian Attitudes toward the World Religions, 1985)

“Transcendent Unity of Religions” (Frithjof Schuon, 1984)

“Other religions are equally valid ways to the same truth” (John Hicks)

“Other religions speak of different but equally valid truths” (John B. Cobb Jr.)

“Each Religion expresses an important part of the truth” (Raimundo Panikkar)

Pluralism and Liberation (Farid Esack, 1997)

Multiculturalism: Some Definitions

Pluralism and multiculturalism are often overlapped, used interchangeably, but sometimes both mean different things, pluralism can have religious as well as cultural non-religious dimension, but multiculturalism more specifically implies cultural (ethnic, racial, social) diversities.

Multiculturalism emerges from the mid-20 century. Multiculturalism signifies the approach which tries to give as much representation as possible, within legal, political, and educational institutions, to minority cultures. Multiculturalism poses a threat to the social order, removes the foundations for civil obedience. Multiculturalism constitutes an attempt to reduce Western civilization to the status of a culture. The principle influence of multiculturalism has been on the curriculum, especially in the universities, where multiculturalists argue that study in the humanities has focused exclusively on the work of dead white European males and ignored the achievements of other cultures. (Roger Scruton, A Dictionary of Political Thought, 1996)

Neither universities or policies can effectively pursue their valued ends without mutual respect among the various cultures they contain. Some differences – for example, racism and anti-Semitism – ought not to be respected even if expressions of racist and anti-Semitic views must be tolerated; Multicultural societies and communities that stand for the freedom and equality of all people rest upon mutual respect for reasonable intellectual, political, and cultural differences. (Amy Gutmann, Multiculturalism, 1994)

In the private sphere: my own identity crucially depends on my dialogical relations with others. In the public sphere, politics of multiculturalism, politics of recognition, politics of universalism (difference-blind fashion), politics of difference, politics of equal dignity: individualized identities, the notion of authenticity, equalization of rights and entitlements (Charles Taylor, “Politics of Recognition”, in Multiculturalism, 1994)

Pluralism, Religious Pluralism in Indonesia

Religious pluralism is equally complex concept; it is a Western word, but Indonesia has similar term signifying pluralism: Bhineka Tunggal Ika, Pancasila as the state philosophy, dipahami berbeda-beda, sering menjadi alat kekuasaan untuk mempertahankan status quo atau mainstream

Persoalan-persoalan antarumat beragama di Indonesia sangat komples: Kristenisasi dan Islamisasi, perkawinan beda agama, doa antaragama, pengadilan agama, pendidikan, Tujuh patah kata Piagam Jakarta, bentrok fisik Kristen-Islam,

Indonesian Scholarship on pluralism:

Nurcholish Madjid: pertama, sikap yang ekslusif dalam melihat agama lain (agama-agama lain adalah jalan yang salah, yang menyesatkan para pengikutnya), keduam sikap inklusif (agama-agama lain adalah bentuk implisit agama kita), dan ketiga, sikap pluralis (Agama-agama lain adalah jalan yang sama-sama sah untuk mencapai Kebenaran yang Sama, Agama-agama lain berbicara secara berbeda tetapi merupakan kebenaran-kebenaran yang sama sah, setiap agama mengekspresikan bagian penting sebuah Kebenaran), dialog antaragama berbasis keyakinan kepada seluruh para nabi dan rasul, syir’ah dan minhaj yang berbeda-beda, berlomba-lomba dalam kebajikan. (Nurcholish Madjid, 1998)

Pluralisme tidak dapat dipahami hanya dengan mengatakan masyarakat kita majemuk, pluralisme juga tida boleh dipahami sekedar kebaikan negative, sekedar menyingkirkan fanatisme, pluralisme harus dipahami sebagai pertalian sejati kebinekaan dalam ikatan-ikatan keadaban (genuine engagement of diversities within the bonds of civility) (1999)

Alwi Shihab: toleransi awal dari pluralisme. 1. pluralisme tidak semata menunjuk pada kenyataan adanya kemajemukan, harus ada keterlibatan aktif, 2. pluralisme harus dibedakan dengan kosmopolitanisme (kota Kosmopolitan tanpa interaksi aktif), 3. pluralisme tidak sama dengan relativisme (semua agama adalah sama), 4. pluralisme agama bukan sinkretisme. Seorang pluralis membuka diri, belajar dan menghormati penganut lain, tapi committed terhadap agama yang dianutnya (Islam Inklusif, 1997)

Budi Munawwar Rahman: Islam Pluralis (2001), Muhamad Ali, Teologi Pluralis-Multikultural (2003)

Conclusions

Pluralism is a complex but useful concept in explaining many issues related to human interaction and relationships;

Pluralism, religious pluralism, multiculturalism each means different thing for different people, but it has basic common notion: acceptance of the existence of diversity; the reading of texts and the role of context shapes such plurality of definitions of religious pluralism; Religious pluralism is never purely religious matter; it involves politics for the large extent

Religious pluralism in the context of Indonesia should be fundamentally agreed by the government and civil society, but its application can be contextual; the challenge remains, that is how to reconcile between recognition of difference and respect of universal substantive values.

As suggestion, we need to develop comparative religions/history of religions, national history of religions, world history of religions, studies of local cases of interfaith meetings and dialogues, interreligious prayers, interfaith marriages, religious pluralism and law, pluralism and education, studies of the history of religious pluralism in Indonesia, and other pluralism-related issues.

Photo: in a Buddhist Temple, Kelantan, Malaysia, with Abdullah Che Tengah, June 2005

Monday, August 28, 2006

The Case for Islamo-Christian Civilization

The Jakarta Post, March 2, 2005

Muhamad Ali

What would most people think when they read or hear the phrase Islamo-Christian Civilization? Many Muslims and Christians would likely bristle at the very idea it seems to embody, and others will look suspiciously at the omission of “Judeo-“ from the phrase. Many more would suspect that this is simply impossible theologically and historically. Why Islamo-Christian Civilization?

Aren’t Christianity and Islam distinct and separated theologically and historically?

Challenging Huntington’s Clash of Civilizations, Prof Richard Bulliet wrote an enlightening work entitled “The Case for Islamo-Christian Civilization” (2004). Such phrases as Children of Abraham, Semitic Scripturalism, or Abrahamic Religions seem to do quite well for the Islamo-Judeo-Christian Civilization, but an Islamo-Christian civilization implies that Muslims and Christians shared the past, present and future. Conventional wisdom maintains that the differences between Islam and Christianity are irreconcilable. Bulliet looks beneath the rhetoric of hatred and misunderstanding to challenge the prevailing and misleading views of Islamic history and Clash of Civilizations. Bulliet argued that the sibling Christian-Muslim societies begin at the same time, go through the same developmental stages and confront the same internal challenges. Yet as Christianity grows rich and powerful, Islam finds success around the globe but falls behind in wealth and power.

According to Bulliet, the term Islamo-Christian civilization denotes a prolonged and fateful intertwining of sibling societies enjoying sovereignty in neighboring geographical regions and following parallel historical trajectories. Neither the Muslim nor the Christian historical path can be fully understood without relation to the other.

There is still a tendency to say that Muslims are less open to new ideas than Christian Westerners and that Muslims are more prone to conflict between themselves and to hate non-Muslims. Many Westerners often view the actual life of backward, poor, and sometimes violent Muslims in the light of the ideal peaceful separation between religion and the church in the West. On the other hand, many Muslims still blame the West as the cause of their backwardness materially and their moral crisis simply by referring to, for example, sexual freedom appearing in mass media. As Bulliet suggests, Westerners characterize militant Muslims as the dominant voice and scarcely recognize the presence of moderate and liberal minds. Muslims on the other hand, see the West as the secular land of sin, salesmanship, and superficiality. Both sides seem unaware of the admirable positive qualities that most Muslims and Westerners exhibit in their daily life.

Westerners do not include Islam in their civilization mainly because they are heirs to a Christian construction of history that is deliberately exclusive. Western Christendom regards Islam as a malevolent Other for many centuries and has invented any number of reasons for holding this view.

In the academic circle in the West, we tend to read European or Western history in Euro-centric perspective as if the world is only the West. On the other hand, Muslims have their own historical reading as if there is only an Islamic history and there is no interaction between them and others. I have not find any single work on world history considering Islam, Christianity and others as one historical actor in a shared civilization. In other words, there is no a truly shared world history being written and promoted.

In Indonesia, historiography tends to be exclusive. For example, Christianity has been regarded as a colonial religion; a religion that was carried and preached by the Dutch colonials –and English, Germans, Americans. This has become the main obstacle for mutual understanding among Muslims and Christians in Indonesia. The historical fact is that Christianization is not always part of colonial enterprises. There were Christians who opposed Dutch colonialism; and when some of them did not they were engaged in education and cultural development. Many of them were independent missionaries, just like Muslim preachers. Understanding this more objective history is crucial in rehabilitating hidden distrust between Muslims and Christians.

It is true that the majority of Indonesians today are Muslims, but this does not necessarily mean that non-Muslims, including Christians did not play a part in Indonesian independence and postcolonial local and national development. Majority-minority perspective has often obscured the fact that significant contribution to shared economic, cultural, and political development has been continuously made by different religious leaders and communities.

Indonesia has actually witnessed peaceful coexistence between different religious communities. News reports and scholarly research on inter-religious conflicts as taking place in some parts of Indonesia should not overlook the more consistent and wider-range situation of inter-religious cohabitation. Religious civil societies have been promoting peaceful coexistence, but non-specifically religious organizations and individuals, often without any religious affiliation, have equally demonstrated how they could work together in their economic, educational, political and cultural activities.

Such economic, political, and cultural shared experiences are the best example of how Islamo-Christian civilization in Indonesia is neither something foreign nor impossible to maintain in the future. In social, economic, and political relationships, Muslims and Christians have long collaborated in both local and national levels. This kind of Islamo-Christian civilization that Richard Bulliet envisages has apparently worked quite well in Indonesia, but a shared religious history in which Muslims, Christians as well as other religious communities played the same role is still far from reality. A challenging effort is how to establish a shared history of civilization in which Christian and Muslim cultures are actually integrated in Indonesia.

In addition, religious pluralism in the sense that good Christians and Muslims are not infidels to each other and that good Christians and Muslims can get salvation and happiness is much more difficult for Muslims and Christians to adhere. For example, a Christian who works with a Muslim in a company can be very friendly, but when it comes to their belief they tend to regard the others as infidels and not worthy of salvation in the hereafter.

Therefore, to suggest an Islamo-Christian civilization should consider different levels of human relations: material-economic, but also religious-moral. Our challenge is how to rethink our own belief in light of other beliefs and to reinterpret our ritualistic and textual texts in light of more contextual, general and shared reading of history. Thus, to be tolerant is not simply to pretend to be good to other religious individuals and communities at the social and economic levels, but also to regard the others as we regard ourselves in terms of God’s salvation and blessings here in the world and in the hereafter.

The idea of Islamo-Christian civilization is constructive (and can be widened to include other religions too), but it rests more immediately on the need of more specifically Christians and Muslims in Indonesia and elsewhere to find common ground at a time when suspicion, fear, draconian government action and demagoguery increasingly threaten to divide them.

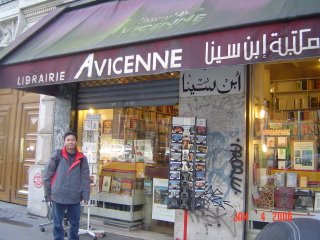

The photo: in front of a bookstore called Avicenne in Paris, Dec 2005

Sunday, August 27, 2006

Saturday, August 26, 2006

Happy to be Back to Hawaii

Aloha,

It is very nice to be back to Hawaii, after one and half year of my fieldwork and travel to parts of Indonesia, parts of Malaysia, Holland, France, and Belgium. We see old faces, but more new faces at Hale Manoa and Hawaii. It is also nice to know new friends. I hope and pray for a better and more wonderful life for us and everyone now and in the future.

Mahalo,

Hale Manoa, 1202E

The Photo: I stood in front of KILTV, Leiden.

Monday, August 14, 2006

Strengthening Moderate Islam in Indonesia

The Jakarta Post, 4 August 2006

STRENGTHENING MODERATE ISLAM IN INDONESIA

Muhamad Ali

Who are moderate Muslims in Indonesia today? This question has been controversial and debatable depending on one’s political and religious perspective. It seems that most scholars and people at home and abroad share the conviction that most Muslims in Indonesia are tolerant and moderate, but many still find it difficult to identify who they are, what they actually do, and what their future is.

There is semantic issue in what the term implies, but more importantly, one’s perspective shapes his or her view on what moderate Islam is and who moderate Muslims are. For some, Islam is inherently moderate and all Muslims, without exception are therefore moderate in any time and in any place, there are no radical, no fundamentalist, no moderate no liberal. This aim is in contradiction with the plurality of the world naturally and culturally. This conviction is simply based on faith, believing that our faith is always true and good and therefore those who have this faith are automatically true and good, even the truest and best. In reality that is not the case. There are Muslims who are not moderate. But who are they?